An Apology to My Space Camp Counselor

29 Years Too Late

I used to blame the Lucky Charms, but it’s time to take responsibility.

Toward the end of third grade, the teacher asked us to make a construction paper cutout of what we wanted to be when we grew up. My deskmate waffled between doctor, lawyer, and firefighter, but I already knew my answer. After a frenzy of Fiskars scissors and Elmer’s glue, I lined up to pin my masterpiece on the classroom wall. The teacher’s aide passed by and squinted at my work. “Marc... what’s that supposed to be?”

"An astronaut," I proudly declared. I'd been watching the Star Wars trilogy VHS tapes on repeat for three years by that point, and I knew I was destined to go to space.

“Oh, that’s... With your eyes... I don't think you can...” She caught herself. "But you never know!" The damage had already been done. If she couldn’t imagine it, then I wasn’t allowed to either.

I grew up in one of those “you can be anything you want to be if you just work hard enough” suburbs of the early ‘90s. My shelves buckled under all the participation trophies. Even as a visually impaired kid, I had never banged my head this hard on the ceiling of other people's expectations before. It fucking hurt. My cheeks blistered with shame. I knew I had bad eyesight. I knew it would be an uphill battle to convince NASA to let me fly a spaceship. But I had about the same chance of being the first visually impaired astronaut as Kevin P. had of being the first bedwetting President, and no one said shit to him.

I hid my construction paper cutout in my desk and made up some excuse about needing more time because of my eyes. I stopped watching Star Wars (as much). I tried to find some other path for myself down here on Earth, a planet where people squash your dreams before you even get a chance to pin them to the corkboard.

Then I discovered that Space Camp occasionally offered scholarships for blind or visually impaired kids. Neil Armstrong might as well have shown up at my door with a job offer by the way I reacted. Finally, my chance to prove to all the teacher’s aides of the world that I could do this—that I could do anything. The glossy brochure pictured two kids sitting in the cockpit of a life-size shuttle simulator. I decided then that I would sit in one of those seats.

The application was a pain in the ass—a term I learned from my father during the process. Doctor’s notes, short answer questions, financial aid verification, and an essay about why I deserved a scholarship. My parents, who had suffered through the rest of the forms, said I had to complete the essay on my own.

Why did I deserve the scholarship? I knew from my research that astronauts often had military backgrounds, engineering skills, and excelled in math and science. I had none of those, so why me? Because I loved science fiction stories? Because the gravity of my insecurity and everyone else’s misconceptions was crushing me, and the only escape I could think of was to leave the whole planet behind? Because I used to believe the world was fair and reasonable and good before this diagnosis smashed into it like a rogue asteroid, and a partially-paid trip to Space Camp was the only sign that any shred of justice survived?

Not that I could comprehend those tectonic rumblings at the time. Instead, I sat there trying to make sense of the blank page like an ancient soothsayer trying to make sense of an eclipse. At the last minute, I hastily wrote a short story called “Spaceman Sam”—now lost to history, but which, even at the time, I knew was kinda lame—and stapled it to the packet where the essay was supposed to go. For some reason, they accepted it.

That summer, just after my tenth birthday, my parents put me on a plane alone for a week in Huntsville, Alabama. I watched out the window as the plane broke through the clouds, Chicago dwindling in the distance, the atmosphere getting thinner and thinner, the freedom of space just a few miles above.

The van from the airport lurched to a stop outside the U.S. Space & Rocket Center. The driver turned back to the handful of nervous kids, most of us away from home for the first time. “There are counselors by the shuttle to help you check in.”

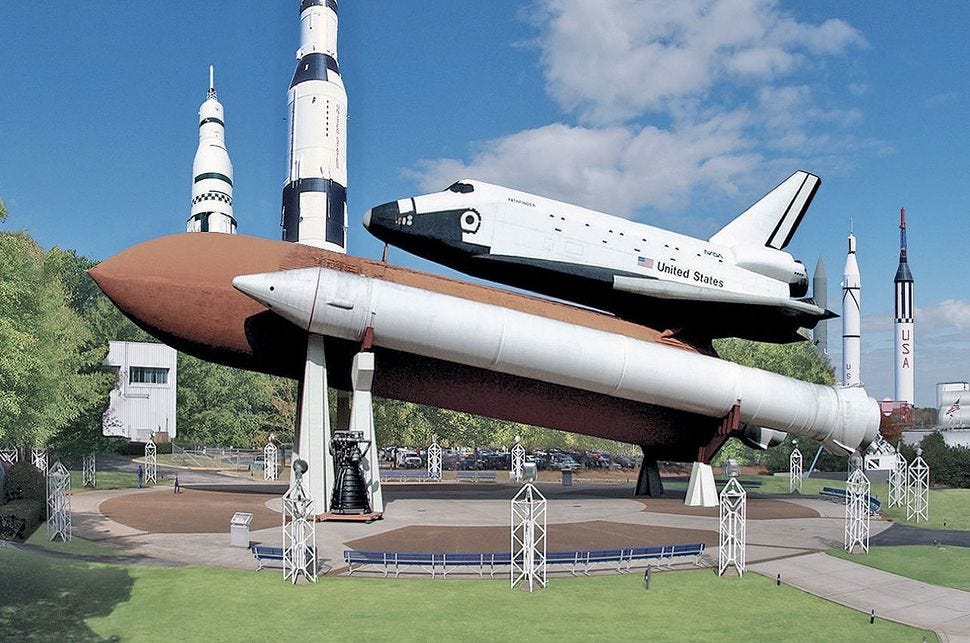

“Shuttle?” I asked. He just smiled and opened the van door, and we got our first glimpse of the shiny modern facade of the U.S. Space & Rocket Center and the futuristic tubular dormitories. And there, standing on pylons over the plaza, was the Space Shuttle Pathfinder, gleaming white and black in the Alabama sun. An actual real-life space shuttle, complete with fuel tank and booster rockets, so close even I could see it.

I fell in with the throng of campers coalescing in Pathfinder’s shadow, hundreds of voices echoing off the shuttle’s bulbous orange fuel tank. Clipboard-wielding volunteers swooped in to direct us—“Program? Age? Name? Over there.” I squeezed into a cluster of other nine-to-eleven-year-olds being checked in by our counselor, Kyle. Kyle was a gregarious skateboard guy with a tangled poof of dyed-black hair. He couldn’t have been older than 20 and spent most of his time doing Simpsons quotes to impress the female counselors, but to us, he was a paragon of adulthood, purpose, and success.

“Dude, welcome!” Kyle said after checking my name off on his list. “Sci-Vis Week is my favorite.” I was confused. Sci-Vis Week? Kyle explained: “It’s when all the visually impaired campers come.”

All? I didn’t know how many scholarships they gave out, but I figured we were vying for spots throughout the summer. I really should have read the brochure past the picture of the cockpit. I’d barely ever met another blind person before, let alone one my age. I looked around. A boy next to me had a white cane. Another wore thick sunglasses. For my entire life, I had been “the blind one”, and here I was surrounded by people just like me. Luckily, they couldn’t see me gaping.

Kyle led us on a tour of the Space & Rocket Center, the grounds, and the dorms—which they called “habitats” and dressed up to look like we were sleeping inside a space station. Kyle paused patiently at every turn and curb to let his charges navigate. Without anyone needing to ask, those of us who could see better offered the crooks of our arms to those who couldn’t, swapping names, diagnoses, and physical support as we went. It felt strange, new and familiar all at once, like I’d been living on an alien planet for years and finally returned home. One boy had Stargardt’s Disease like me, with no central vision. Two others had RP, the inverse, with central vision but no peripheral. The rest ran the gamut of eye conditions and abilities. Despite my blind spot that had blossomed over the past few years, it became clear that I was one of the better-sighted members of our crew. Emboldened by this discovery, I offered to lead the way to dinner and only got us lost once. In the cafeteria, I got to be the one reading labels on food packages and pointing people to where the condiments were. I was giddy—partially from this new role, partially because the cafeteria stocked Lucky Charms, which I was not allowed to have at home, and I’d already eaten three bowls. For a moment, I forgot all about teacher’s aides and their world and just had fun.

After dinner, Kyle walked us over to the simulator, the crown jewel of Space Camp. There was a room designed like the real Mission Control center in Houston. Through a window in the wall, we could see a kid-scale replica of the interior of a shuttle. I recognized it immediately from the picture in the brochure. Kyle explained that the week of camp builds to a simulated shuttle mission. Each camper would be assigned a real job that someone on a real flight would do, including the crew of the shuttle and the ground control team back in Houston.

Our performance during the activities leading up to the mission would help our counselors decide which role we’d be best suited for. This was my path to the cockpit. I’d done my NASA research, and if I wanted to sit up front, I had two options: the Pilot, who flies the shuttle. And the Commander, who’s in charge of the whole thing. Pilot sounded more fun, but Commander sounded more impressive. I decided I would accept either.

Kyle had to greet some late arrivals, so he dropped us off at a bank of screens with joysticks where we could practice flying and landing a space shuttle—the perfect chance for me to demonstrate my pilot prowess. With an uncharacteristic confidence fueled by processed marshmallows, I volunteered to go first. The shuttle was finicky to fly, at least according to this pixelated 1995 computer game, and we all struggled to keep her in the air. But after a few rounds, I started to get the hang of it. I was in the zone, trying to master the landing, when I realized Kyle was watching.

“Great work, Marc. You almost had that one,” he said, patting my shoulder. I wasn’t used to being the star pupil, and the surge of pride was the closest I’d ever felt to zero-G. I returned triumphantly to my less visually endowed crewmates and received their chorus of “good job”s.

Then Kyle moved to the monitor next to mine. “Nate, perfect landing!” He high-fived the kid at the joystick, a newcomer I hadn’t met yet. Jealousy slithered out of the pit of my stomach and coiled itself around my pride. I moved my blind spot aside to get a better look at this “Nate”. He was a handsome 11-year-old with bushy eyebrows and a good-natured grin, the kind of earnest, affable guy it was impossible to dislike. That didn’t stop me from trying. Especially when I heard he had perfect 20/20 vision.

Nate had gotten in late with his blind friend R.J., whose parents were worried about sending their disabled son to Alabama alone. So they paid for Nic and his immaculate eyes to tag along. R.J. was somehow even more earnest and even more affable than Nate. When someone asked him what he was most excited about at Space Camp, he even said, “To meet all of you!” The two newcomers instantly became the social and emotional heart of our ragtag crew. Neither of them knew they had just become my nemeses.

Over the next few days, we saw inside a supersonic jet, a Saturn V rocket, and the landing capsule from a real Apollo mission. We participated in fun-filled, space-themed activities to teach us what it was like to be a real astronaut. I, of course, focused all my energies on outshining Nate. I practiced my piloting (more than Nate did). I bounced in the Moon Gravity Chair (higher than Nate). I took two spins on the Multi-Axis Trainer (twice as many as Nate!) until I almost puked. I ate seven bowls of Lucky Charms (Nate didn’t even eat one!). A few days and 4,000 marshmallows later, Kyle announced our assignments for the simulator mission. I listened as he listed off the Mission Specialists, the Engineers, relieved that I hadn’t been relegated to one of these lesser positions. Finally, he got to the cockpit. The Commander would be... R.J. And the pilot would be... Nate. Something broke inside me. I was so busy stewing that I didn’t even hear Kyle call my name.

“And last but not least, Marc! ...Marc?"

“Uh, yeah?”

“You’ll be the Capcom!”

There must have been a mistake. Capcom was objectively the lamest role in the whole simulation. It’s the person who sits in Mission Control and repeats over the radio the things that people with real jobs say. Like you wait for the Flight Director to say, “We are go for launch,” and then you turn on your microphone and say, “We are go for launch.” After days of busting my ass on every activity this was what I got? So I did what any entitled 10-year-old on his own for the first time and jacked up on high-fructose corn syrup would do: I threw a fit. I ran into the hallway. I wailed about how I needed to be in the cockpit, how this was my only chance. It wasn’t fair that Nate got to be Pilot just because he could see. And how could R.J. be Commander when he was completely blind?—Yep, I went there. I unleashed the full, confused, pre-pubescent torrent of my self-pity on poor Kyle, a nerdy teenager at his summer job just trying to look cool in front of some girls.

The thing was, as a disabled kid, this kind of hysterics had a pretty solid track record. Teachers and coaches felt so bad about how hard my disabled life must be that they usually just caved. Not Kyle. He listened politely through the worst of it. Then gently told me I couldn’t change roles. I stomped. I cried. I stormed out to the cafeteria and drowned my sorrows in hearts, stars, horseshoes, clovers and blue moons, pots of gold, and rainbows, and red balloons.

I’d come halfway across the country to live this dream and blew the whole thing. The worst part was that the other kids in my group heard every word. Kyle found me slurping up the sugary milk at the bottom of my single-use plastic bowl. As a peace offering, he promised me a “leadership position” in the Mars Exploration activity on the last day. That didn’t sound nearly as cool, but I knew it was the best I was going to get.

The next morning, I took my seat in Mission Control. Thanks to my poor vision, I couldn’t see the withering glares from my colleagues. I didn’t have to. Their disdain was palpable. The Capcom is supposed to connect the two sides of the mission. I had pushed everyone away.

Our mission was a disaster. We were supposed to take off, connect with the Hubble, send our Mission Specialists out to repair it, and then return safely home. We crashed into the Hubble, then sent our repair crew out. But R.J. dropped his braille flight manual, which the printers neglected to put braille page numbers on, so nobody knew which order the different steps should go in. We accidentally left our Mission Specialists floating outside. Then we incinerated them and the Hubble with our rockets as we headed back. The shuttle burned up on re-entry, and when the counselors gave us a second chance to land, Nate crashed into the runway and the shuttle exploded. The whole thing somehow managed to take an hour longer than scheduled, to the great distress of Kyle and the other groups waiting outside for their turn. At first, I had a bit of schadenfreude about the whole thing. If I had been in the cockpit, things might have gone differently. But as Capcom, I had to keep relaying everyone else’s stress and disappointment, and for the first time it struck me how every kid here was just as passionate about space as I was, how much they had all bonded over the week, and how badly they were all fighting for our underdog disabled mission. I had finally found a place where I belonged and somehow managed to make myself even more of an outsider than I was at home.

I vowed to myself that I would make it up to everyone at the Mars Exploration the next day. As we entered the open room with a spongy red floor, Kyle made a show of appointing me the “Commander” of the mission. In retrospect, I don’t think that role existed prior to my tantrum, and this became clear when the other kids were grouped in threes or fours and set to specific tasks like digging up rocks, measuring soil contents, or running experiments. I was told to “oversee” them—which meant I had nothing to do but walk around in circles, looking over everyone’s shoulders. But I couldn’t see well enough to know what they were doing, and no one wanted me around. When I wandered over to a group, they’d fall silent. If I asked questions, I’d get one-word answers. When I wandered away, they went back to enjoying themselves. Halfway through, I left the Mars room and walked out to the plaza to ugly-cry beneath Pathfinder—which I learned during the week was merely a prototype that, like me, was never meant to fly.

I couldn’t understand how everything had gone so wrong. Space Camp was supposed to be the reward for everything I’d been through over the five years since my Stargardt’s symptoms emerged. My chance to prove everyone wrong. Didn’t I deserve this? Or was that why I had so much trouble writing my essay... because I actually didn’t? I was so desperate to prove myself that I missed out on something far more powerful: a group of people who didn’t ask me to.

I couldn’t understand any of that then, so when Kyle came out to sit with me, I just huffed at him and went back to my habitat. The next morning, I left for the airport without saying goodbye.

Two decades passed before I encountered another group of disabled people. I had just joined the Writers Guild, and my welcome email included a calendar of upcoming events. I couldn’t wait to see all the exclusive screenings and star-studded panels. The first listing was for the Disabled Writers Committee. I didn’t know such a thing existed. Let alone that their next meeting started in four hours.

I took a seat near the back of the room, trying to be inconspicuous. But there weren’t that many of us in those days, so the new guy was pretty obvious. The committee president immediately put me on the spot: “So what brings you here?”

“To meet all of you.”

You may not have reached astronaut status, but in my mind, you and your writing skills are OUT OF THIS WORLD 🚀